OIL GLUT AND PRICE COLLAPSE (1981–1986) AND THE SUPER DOLLAR OF 1980–1984 THE WORLD’S THIRD OIL SHOCK

OIL GLUT AND PRICE COLLAPSE (1981–1986)

Once prices peaked at a record high of $38 per barrel in February 1981, they descended on a six-year slide to reach below $10 in July 1986. Geopolitics again played a role, but this time the price impact was negative.

The outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war in autumn 1980 had the potential to produce further escalation in prices as the war involved two leading world producers of the fuel. But Saudi Arabia, the biggest producer, flooded the world market with inexpensive oil in 1981 and on into the mid-1980s, rais-ing production to make up for the loss of Iranian and Iraqi production.

Once prices peaked at a record high of $38 per barrel in February 1981, they descended on a six-year slide to reach below $10 in July 1986. Geopolitics again played a role, but this time the price impact was negative.

The outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war in autumn 1980 had the potential to produce further escalation in prices as the war involved two leading world producers of the fuel. But Saudi Arabia, the biggest producer, flooded the world market with inexpensive oil in 1981 and on into the mid-1980s, rais-ing production to make up for the loss of Iranian and Iraqi production.

FIGURE 2.5 The pattern of soaring inflation rates followed by contractionary shocks in G7 economies (United States, Japan, Germany, Canada, United Kingdom, France, and Italy) was consistent throughout the three oil shocks, denoted in shaded areas.

Iran’s annual oil production was cut by half, dropping from an average of 19 percent of OPEC’s annual production in the first half of the decade to 10 percent of total production in the second half. Figure 2.6 illustrates the 1978–1981 oil price increase resulting from escalating uncertainty in the Middle East, which was followed by a 74 percent plunge in the ensuing six years.

The other main reason for OPEC’s concerted price cuts was the grad-ual collapse of the world economy in 1980–1982. As the dollar began its five-year ascent in the first half of the 1980s, resulting from soaring U.S. in-terest rates (see next section), falling currencies outside the United States meant rocketing prices of imports from the United States and of higher-priced oil from OPEC. The double whammy of escalating import and oil prices triggered double-digit inflation in Europe and Japan, causing their central banks to embark on aggressive rate hikes at a time of already slow-ing growth and rising unemployment. The result was an economic slump in the industrialized world, giving rise to an unprecedented six consecu-tive annual declines in world imports for crude oil between 1981 and 1986. Global demand plummeted and so did consumption. The impact on oil

Iran’s annual oil production was cut by half, dropping from an average of 19 percent of OPEC’s annual production in the first half of the decade to 10 percent of total production in the second half. Figure 2.6 illustrates the 1978–1981 oil price increase resulting from escalating uncertainty in the Middle East, which was followed by a 74 percent plunge in the ensuing six years.

The other main reason for OPEC’s concerted price cuts was the grad-ual collapse of the world economy in 1980–1982. As the dollar began its five-year ascent in the first half of the 1980s, resulting from soaring U.S. in-terest rates (see next section), falling currencies outside the United States meant rocketing prices of imports from the United States and of higher-priced oil from OPEC. The double whammy of escalating import and oil prices triggered double-digit inflation in Europe and Japan, causing their central banks to embark on aggressive rate hikes at a time of already slow-ing growth and rising unemployment. The result was an economic slump in the industrialized world, giving rise to an unprecedented six consecu-tive annual declines in world imports for crude oil between 1981 and 1986. Global demand plummeted and so did consumption. The impact on oil

FIGURE 2.6 The 1978–1981 oil price shock triggered renewed inflation, causing the U.S. Federal Reserve to respond with soaring interest rates, eventually boosting the value of the U.S. dollar and raising the import burden on nations whose currencies are falling against the greenback. Oil prices began a six-year decline in 1981 due to falling world growth and rising supplies from OPEC.

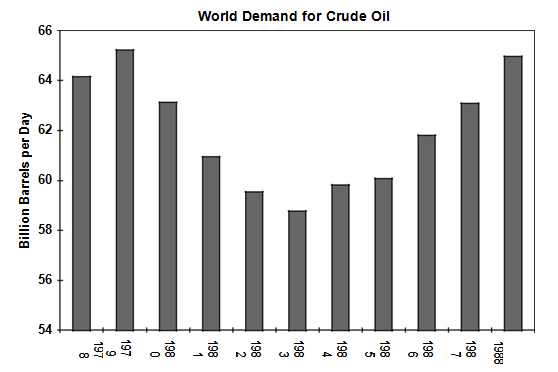

prices was fast and deep. Figure 2.7 illustrates the prominent decline in global oil demand from 1980 to 1984, which played a significant role in ex-acerbating the price plunge.

Besides falling world demand and rising OPEC production as causes of the 1986 oil price plunge, improved conservation measures in the indus-trialized world also played a key factor in transforming the oil shortage into an oil glut. The emergence of cheaper alternatives to OPEC oil in the Alaskan and North Sea fields was also a factor in curtailing demand for the OPEC substance and its price.

THE SUPER DOLLAR OF 1980–1984: THE WORLD’S THIRD OIL SHOCK

The dollar decline of the late 1970s combined with the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war weighed on the international economy in a way that

prices was fast and deep. Figure 2.7 illustrates the prominent decline in global oil demand from 1980 to 1984, which played a significant role in ex-acerbating the price plunge.

Besides falling world demand and rising OPEC production as causes of the 1986 oil price plunge, improved conservation measures in the indus-trialized world also played a key factor in transforming the oil shortage into an oil glut. The emergence of cheaper alternatives to OPEC oil in the Alaskan and North Sea fields was also a factor in curtailing demand for the OPEC substance and its price.

THE SUPER DOLLAR OF 1980–1984: THE WORLD’S THIRD OIL SHOCK

The dollar decline of the late 1970s combined with the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war weighed on the international economy in a way that

FIGURE 2.7 After peaking in 1979, oil demand headed for a four-year decline as central banks pushed interest rates to double digits to fight soaring inflation from the 1978–1980 oil price shock, driving the world economy into recession.

fueled a global inflationary spiral, soaring interest rates, and one of the longest and biggest rallies in the U.S. currency. Although oil prices fell 75 percent between 1981 and 1986, the decline followed a 200 percent price jump in 1979–1980, which was largely caused by the 20 percent slide in the dollar. Such a price surge in a relatively short period of time proved destabilizing for world trade and accelerated global inflation, which was already fed by the dollar declines of 1977–1979.

Aside from OPEC’s oil spikes, inflation was also provoked by the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson’s fiscal expansion to stimulate the Great Society, increased wage demands from labor unions that went beyond pro-ductivity growth, and finally the Federal Reserve’s excessive pump-priming under the government-friendly Chairman Arthur Burns. Inflation hit 11.3 percent, 13.5 percent, and 10.4 percent in 1979, 1980, and 1981 respectively. Price growth also soared in major industrialized nations, reaching 9.5 per-cent, 12.3 percent, and 10.2 percent.

In August 1979, Paul Volcker took the helm at the Fed under the pres-idency of Jimmy Carter when inflation stood at 14 percent. It took two months before the Federal Reserve realized the urgency of adopting drastic measures to fight the destructive effects of an ever-growing price problem on incomes and purchasing power. The policy of targeting interest rates would no longer be effective in stabilizing monetary growth to its desired target of 1.5 to 4.5 percent. In autumn 1979, inflation hit 13 percent, sur-passing the highs of 1974 and attaining levels not seen in 32 years. The Fed funds rate surged to a five-year high of 10.9 percent, and M-1 (the basic aggregate of monetary spending) hit 8.0 percent.

In October 1979, the Federal Reserve made a historical policy shift by adopting a new operating system of targeting money supply rather than interest rates. As it set targets for the quantity of money (money supply) and shifted away from targeting the price of money (interest rates), inter-est rates posted unforeseen sharp fluctuations in their postwar-era levels. Weeks after the Fed made its change, the Fed funds rate jumped to 17 per-cent in one day, dropped to 14 percent the next day, before rebounding again to 17 percent and back down to 10 percent. The new medicine of re-strictive monetarism lasted for two years, driving up the Fed funds rate to as high as 20 percent in 1981.

As U.S. interest rates soared well above those in the industrialized world, so did demand for the greenback, resulting from global investors seeking higher-yielding returns to offset double-digit inflation rates. From January 1980 to February 1985, the U.S. dollar index soared 49 percent. One dollar bought 238.45 yen at the beginning of the period before reaching 259.45 yen five years later. Against the deutsche mark, the dollar climbed from 1.7245 marks to 3.2980 marks while more than doubling against the British pound, from 45 cents to 93 cents.

Figure 2.8 shows the U.S. dollar’s performance against the Japanese yen, deutsche mark, and British pound. As the 1981 oil price peak culmi-nated into broad interest rate cuts in Europe and Japan, their currencies were dragged down against the greenback. The appreciating dollar height-ened the burden on non-U.S. purchasers of oil as they paid for the fuel, priced in higher-valued U.S. dollars, with their depreciating currencies.

The U.S. dollar’s interest rate differential relative to the rest of the world played a major role in the dollar’s ascent. In October 1979, the U.S. Fed funds rate stood at 15.5 percent compared to 7.0 percent in Germany and 6.20 percent in Japan. The U.S. yield advantage soared further as U.S. rates attained the 20 percent mark compared to 9.5 percent and 9.0 percent in Germany and Japan. After a temporary drop to 8.5 percent in June 1980, U.S. rates rebounded back toward the 20 percent mark over the following 10 months as double-digit inflation growth proved hard to abate. Renewed policy tightening once again lifted U.S. rates to twice the level in Germany and Japan as their central banks stopped raising their interest rates. The divergent interest rate picture between the United States and the rest of the world was a principal factor behind the dollar’s haughty advances of the early 1980s.

fueled a global inflationary spiral, soaring interest rates, and one of the longest and biggest rallies in the U.S. currency. Although oil prices fell 75 percent between 1981 and 1986, the decline followed a 200 percent price jump in 1979–1980, which was largely caused by the 20 percent slide in the dollar. Such a price surge in a relatively short period of time proved destabilizing for world trade and accelerated global inflation, which was already fed by the dollar declines of 1977–1979.

Aside from OPEC’s oil spikes, inflation was also provoked by the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson’s fiscal expansion to stimulate the Great Society, increased wage demands from labor unions that went beyond pro-ductivity growth, and finally the Federal Reserve’s excessive pump-priming under the government-friendly Chairman Arthur Burns. Inflation hit 11.3 percent, 13.5 percent, and 10.4 percent in 1979, 1980, and 1981 respectively. Price growth also soared in major industrialized nations, reaching 9.5 per-cent, 12.3 percent, and 10.2 percent.

In August 1979, Paul Volcker took the helm at the Fed under the pres-idency of Jimmy Carter when inflation stood at 14 percent. It took two months before the Federal Reserve realized the urgency of adopting drastic measures to fight the destructive effects of an ever-growing price problem on incomes and purchasing power. The policy of targeting interest rates would no longer be effective in stabilizing monetary growth to its desired target of 1.5 to 4.5 percent. In autumn 1979, inflation hit 13 percent, sur-passing the highs of 1974 and attaining levels not seen in 32 years. The Fed funds rate surged to a five-year high of 10.9 percent, and M-1 (the basic aggregate of monetary spending) hit 8.0 percent.

In October 1979, the Federal Reserve made a historical policy shift by adopting a new operating system of targeting money supply rather than interest rates. As it set targets for the quantity of money (money supply) and shifted away from targeting the price of money (interest rates), inter-est rates posted unforeseen sharp fluctuations in their postwar-era levels. Weeks after the Fed made its change, the Fed funds rate jumped to 17 per-cent in one day, dropped to 14 percent the next day, before rebounding again to 17 percent and back down to 10 percent. The new medicine of re-strictive monetarism lasted for two years, driving up the Fed funds rate to as high as 20 percent in 1981.

As U.S. interest rates soared well above those in the industrialized world, so did demand for the greenback, resulting from global investors seeking higher-yielding returns to offset double-digit inflation rates. From January 1980 to February 1985, the U.S. dollar index soared 49 percent. One dollar bought 238.45 yen at the beginning of the period before reaching 259.45 yen five years later. Against the deutsche mark, the dollar climbed from 1.7245 marks to 3.2980 marks while more than doubling against the British pound, from 45 cents to 93 cents.

Figure 2.8 shows the U.S. dollar’s performance against the Japanese yen, deutsche mark, and British pound. As the 1981 oil price peak culmi-nated into broad interest rate cuts in Europe and Japan, their currencies were dragged down against the greenback. The appreciating dollar height-ened the burden on non-U.S. purchasers of oil as they paid for the fuel, priced in higher-valued U.S. dollars, with their depreciating currencies.

The U.S. dollar’s interest rate differential relative to the rest of the world played a major role in the dollar’s ascent. In October 1979, the U.S. Fed funds rate stood at 15.5 percent compared to 7.0 percent in Germany and 6.20 percent in Japan. The U.S. yield advantage soared further as U.S. rates attained the 20 percent mark compared to 9.5 percent and 9.0 percent in Germany and Japan. After a temporary drop to 8.5 percent in June 1980, U.S. rates rebounded back toward the 20 percent mark over the following 10 months as double-digit inflation growth proved hard to abate. Renewed policy tightening once again lifted U.S. rates to twice the level in Germany and Japan as their central banks stopped raising their interest rates. The divergent interest rate picture between the United States and the rest of the world was a principal factor behind the dollar’s haughty advances of the early 1980s.

FIGURE 2.8 The U.S. dollar soared during the first half of the 1980s due to higher U.S. interest rates and struggling economies su?ering from the high dollar cost of oil imports.

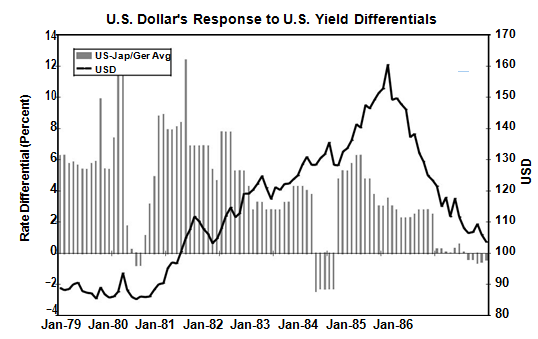

Figure 2.9 illustrates the role of the widening U.S. interest rate advan-tage in spurring the U.S. dollar’s recovery. The currency, as in the case of most currencies, rallies not only when U.S. rates are on the rise but partic-ularly when they are closing the margin below their foreign counterparts. The Federal Reserve’s tightening policy shifted toward targeting money supply, while letting interest rates double to 20 percent. The rapid gains in U.S. yields increased appetite for holding dollars.

The 1979–1980 inflationary spiral forced major central banks into dou-bling their interest rates, and the world economy came to an abrupt halt in early 1981. The combination of soaring inflation and rising unemployment was a vicious pattern that pitted central banks against their governments, with the former focusing on combating inflation via higher interest rates and the latter aiming to fight unemployment through easing fiscal policies. The economic treatment of Paul Volcker’s two-year dosage of hard mon-etary medicine succeeded in vanquishing inflation from its 30-year highs, but at the expense of a two-year recession that sent unemployment to a postwar high of 10.7 percent.

As the recession deepened in 1980–1981 and inflation peaked by the end of 1980, the Fed began a three-year easing campaign, slashing rates from 20 percent in May 1981 to 3 percent in February 1984. Despite the 87 percent decline in interest rates, the dollar was unrelenting dur-ing this three-year period, doubling against the deutsche mark and the British pound, while gaining 9 percent against the Japanese yen. The more

Figure 2.9 illustrates the role of the widening U.S. interest rate advan-tage in spurring the U.S. dollar’s recovery. The currency, as in the case of most currencies, rallies not only when U.S. rates are on the rise but partic-ularly when they are closing the margin below their foreign counterparts. The Federal Reserve’s tightening policy shifted toward targeting money supply, while letting interest rates double to 20 percent. The rapid gains in U.S. yields increased appetite for holding dollars.

The 1979–1980 inflationary spiral forced major central banks into dou-bling their interest rates, and the world economy came to an abrupt halt in early 1981. The combination of soaring inflation and rising unemployment was a vicious pattern that pitted central banks against their governments, with the former focusing on combating inflation via higher interest rates and the latter aiming to fight unemployment through easing fiscal policies. The economic treatment of Paul Volcker’s two-year dosage of hard mon-etary medicine succeeded in vanquishing inflation from its 30-year highs, but at the expense of a two-year recession that sent unemployment to a postwar high of 10.7 percent.

As the recession deepened in 1980–1981 and inflation peaked by the end of 1980, the Fed began a three-year easing campaign, slashing rates from 20 percent in May 1981 to 3 percent in February 1984. Despite the 87 percent decline in interest rates, the dollar was unrelenting dur-ing this three-year period, doubling against the deutsche mark and the British pound, while gaining 9 percent against the Japanese yen. The more

FIGURE 2.9 The U.S. dollar soared as rapid rate hikes increased appetite for hold-ing dollars. The USD Index is plotted against a graph representing the Fed funds rate minus the average rate of Japanese and West German interest rates.

modest gains against the yen were attributed to the positive impact of Japan’s surging exports on its currency and the fact that Japanese rates had ceased falling earlier in the period than had their German and British counterparts.

modest gains against the yen were attributed to the positive impact of Japan’s surging exports on its currency and the fact that Japanese rates had ceased falling earlier in the period than had their German and British counterparts.

PLEASE READ ALSO : WORLD INTERVENES AGAINST STRONG DOLLAR (1985–1987) AND FALLING DOLLAR AND OIL: A BOON FOR NON-USD IMPORTERS

To the rest of the world, the soaring dollar meant falling currencies and rising inflation. The second oil shock of 1978–1979 was already driv-ing up the oil import bill on world economies. As the dollar strengthened, nations had to spend more of their depreciating currencies to import high-dollar-priced goods. The externally driven inflation forced central banks to maintain interest rates higher than their domestic economies warranted, especially as nations such as West Germany and Japan were tightening their fiscal policies to trim down swelling budget deficits. Already in a campaign to fight the inflationary pressures of soaring oil, West Germany further raised rates from 3.5 percent in 1979 to 9.5 percent in 1980, caus-ing a two-year contraction in economic growth, which included a doubling of unemployment to 2.3 million by 1982. Of the unemployed 32 million in OECD nations, half were from Europe. There was no growth contraction in Japan, largely due to the nation’s burgeoning exports industry cushion-ing the overall economy. But GDP growth did enter the range of a growth recession, which is defined as a growth rate below 3 percent.

To the rest of the world, the soaring dollar meant falling currencies and rising inflation. The second oil shock of 1978–1979 was already driv-ing up the oil import bill on world economies. As the dollar strengthened, nations had to spend more of their depreciating currencies to import high-dollar-priced goods. The externally driven inflation forced central banks to maintain interest rates higher than their domestic economies warranted, especially as nations such as West Germany and Japan were tightening their fiscal policies to trim down swelling budget deficits. Already in a campaign to fight the inflationary pressures of soaring oil, West Germany further raised rates from 3.5 percent in 1979 to 9.5 percent in 1980, caus-ing a two-year contraction in economic growth, which included a doubling of unemployment to 2.3 million by 1982. Of the unemployed 32 million in OECD nations, half were from Europe. There was no growth contraction in Japan, largely due to the nation’s burgeoning exports industry cushion-ing the overall economy. But GDP growth did enter the range of a growth recession, which is defined as a growth rate below 3 percent.

0 Response to "OIL GLUT AND PRICE COLLAPSE (1981–1986) AND THE SUPER DOLLAR OF 1980–1984 THE WORLD’S THIRD OIL SHOCK"

Post a Comment