FIRST OIL SHOCK (1973–1974), THE FIRST DOLLAR CRISIS (1977–1979) AND SECOND OIL SHOCK (1978–1980)

FIRST OIL SHOCK (1973–1974)

As the dollar tumbled in world markets, OPEC suffered from two fronts: being paid in a rapidly depreciating U.S. dollar, and facing higher costs of its imports as world inflation pushed up prices for commodities and indus-trialized goods. The Vietnam War played a key factor in lifting U.S. infla-tion to 4.2 percent in 1968 from 2.7 percent in 1967. In 1969 inflation hit 5.4 percent before reaching as high as 6.2 percent in 1970. The 47 percent increase in U.S. prices was exacerbated by the dollar decline at the turn of the decade.

No surprise that in early December 1970, the oil cartel began its first formal discussions about price increases, resulting from changes in foreign exchange rates. In the three years leading to the 1973 oil embargo, OPEC had made several price increases aimed at offsetting the declining value of oil receipts from the falling U.S. dollar. At its 1970 annual conference, OPEC passed a resolution expressing concern about “worldwide inflation and the ever widening gap existing between the prices of capital and man-ufactured goods and those of petroleum.” Price increases were also ac-companied by allowances for rising inflation. In 1971, 1972, and 1973, oil producers increased prices by 2.5 percent, 8.5 percent, and 5.7 percent, respectively.

One cannot assess the inflationary pressures triggering OPEC’s price hikes in 1971 without addressing the expansive monetary policy pursued under the Fed Chairmanship of Arthur Burns. After Nixon became presi-dent in 1968, he appointed Burns as Fed Chairman in 1970—the same per-son who had advised him to cut interest rates prior to the 1960 election campaign. Burns had also served as a cabinet-rank counselor to the pres-ident on all economic issues for the year before becoming chairman of the independent Federal Reserve. Burns’ pump-priming, aimed at ensur-ing Nixon a second term, catapulted money supply growth to 11 percent in the summer leading to the 1972 election, four times greater than the prior year. The inflationary consequences of those policies have played an unequivocally major role in the U.S. failure to maintain a fixed exchangerate regime against gold, eventually triggering the devaluation of the U.S.currency.

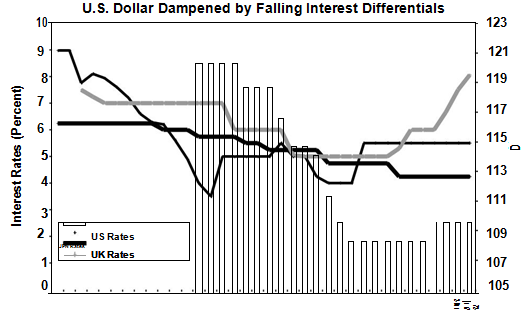

Figure 2.2 illustrates how Arthur Burns’ easing monetary policy drove U.S. interest rates below those of the rest of the world, thus reducing the yield reward of the U.S. dollar and eroding 10 percent from its value be-tween 1971 and 1972. Oil producers no longer content with being paid in depreciating dollars had to push up prices.

Against the backdrop of rising oil prices and a falling U.S. dollar in the first 2.5 years of the decade, the oil embargo of October 1973 precipi-tated the oil price hike on a global scale. Between 1973 and 1974, oil rose fourfold to nearly $12 per barrel, prompting sharp run-ups in U.S. gasoline prices and an abrupt decline in consumer demand. The plummeting dol-lar amplified the surge in prices and doubled inflation to an annual rate of 6.3 percent in major industrial economies, from 3.3 percent in 1972. In 1974, U.S. inflation soared to 11.0 percent while that of major industrial economies hit 13.7 percent, from 7.9 percent the prior year. In 1974–1975, the U.S. and major industrialized economies descended into recession.

Once U.S. inflation peaked at 12.3 percent in 1974, the dollar began a gradual rebound from March 1975 to May 1976, coinciding with a global recovery after nearly two years of recession. By the time the Fed halted its one-year easing campaign in summer 1975, gross domestic product (GDP)

As the dollar tumbled in world markets, OPEC suffered from two fronts: being paid in a rapidly depreciating U.S. dollar, and facing higher costs of its imports as world inflation pushed up prices for commodities and indus-trialized goods. The Vietnam War played a key factor in lifting U.S. infla-tion to 4.2 percent in 1968 from 2.7 percent in 1967. In 1969 inflation hit 5.4 percent before reaching as high as 6.2 percent in 1970. The 47 percent increase in U.S. prices was exacerbated by the dollar decline at the turn of the decade.

No surprise that in early December 1970, the oil cartel began its first formal discussions about price increases, resulting from changes in foreign exchange rates. In the three years leading to the 1973 oil embargo, OPEC had made several price increases aimed at offsetting the declining value of oil receipts from the falling U.S. dollar. At its 1970 annual conference, OPEC passed a resolution expressing concern about “worldwide inflation and the ever widening gap existing between the prices of capital and man-ufactured goods and those of petroleum.” Price increases were also ac-companied by allowances for rising inflation. In 1971, 1972, and 1973, oil producers increased prices by 2.5 percent, 8.5 percent, and 5.7 percent, respectively.

One cannot assess the inflationary pressures triggering OPEC’s price hikes in 1971 without addressing the expansive monetary policy pursued under the Fed Chairmanship of Arthur Burns. After Nixon became presi-dent in 1968, he appointed Burns as Fed Chairman in 1970—the same per-son who had advised him to cut interest rates prior to the 1960 election campaign. Burns had also served as a cabinet-rank counselor to the pres-ident on all economic issues for the year before becoming chairman of the independent Federal Reserve. Burns’ pump-priming, aimed at ensur-ing Nixon a second term, catapulted money supply growth to 11 percent in the summer leading to the 1972 election, four times greater than the prior year. The inflationary consequences of those policies have played an unequivocally major role in the U.S. failure to maintain a fixed exchangerate regime against gold, eventually triggering the devaluation of the U.S.currency.

Figure 2.2 illustrates how Arthur Burns’ easing monetary policy drove U.S. interest rates below those of the rest of the world, thus reducing the yield reward of the U.S. dollar and eroding 10 percent from its value be-tween 1971 and 1972. Oil producers no longer content with being paid in depreciating dollars had to push up prices.

Against the backdrop of rising oil prices and a falling U.S. dollar in the first 2.5 years of the decade, the oil embargo of October 1973 precipi-tated the oil price hike on a global scale. Between 1973 and 1974, oil rose fourfold to nearly $12 per barrel, prompting sharp run-ups in U.S. gasoline prices and an abrupt decline in consumer demand. The plummeting dol-lar amplified the surge in prices and doubled inflation to an annual rate of 6.3 percent in major industrial economies, from 3.3 percent in 1972. In 1974, U.S. inflation soared to 11.0 percent while that of major industrial economies hit 13.7 percent, from 7.9 percent the prior year. In 1974–1975, the U.S. and major industrialized economies descended into recession.

Once U.S. inflation peaked at 12.3 percent in 1974, the dollar began a gradual rebound from March 1975 to May 1976, coinciding with a global recovery after nearly two years of recession. By the time the Fed halted its one-year easing campaign in summer 1975, gross domestic product (GDP)

FIGURE 2.2 Easing U.S. monetary policy in 1970–1972 played a major role in the U.S. dollar’s decline, stirring up inflation and encouraging OPEC to boost oil prices.

growth in the major industrialized economies rose 5 percent, thanks partly to a 5.3 percent increase in U.S. growth. The recovery lifted the dollar be-tween summer 1975 and summer 1976, propelling the currency by 28 per-cent against the British pound, 10 percent against the deutsche mark, and 6 percent against the yen. The notable rise versus the pound was especially driven by soaring inflation in the United Kingdom, lifting the retail price index by as high as 27.0 percent in August 1975.

THE FIRST DOLLAR CRISIS (1977–1979)

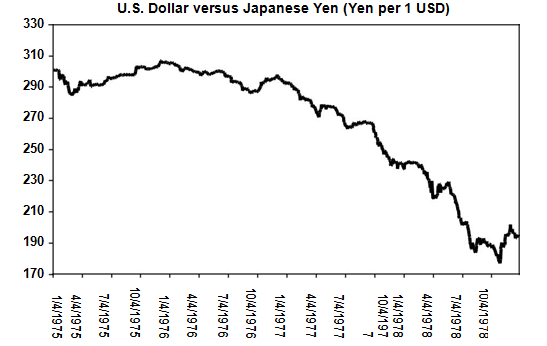

The U.S. dollar rebound of the mid-1970s came to a halt in summer 1976. What followed in the second half of the decade would be a five-year de-cline in the currency, unprecedented in the new post–gold standard era. Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign against Gerald Ford sought to lift the U.S. economy from its slowdown in the second half of 1976. Carter’s currency policy was famously based on the talking down of the U.S. dollar, especially through his outspoken Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal, who pressured the Fed into monetary policy easing. The slide was accel-erated in June 1977 when Blumenthal talked down the dollar after a meet-ing with his German and Japanese counterparts. The new policy sent the dollar tumbling more than 20 percent between January 1977 and October 1978, a dramatic plunge by postwar standards. Figure 2.3 shows how the

growth in the major industrialized economies rose 5 percent, thanks partly to a 5.3 percent increase in U.S. growth. The recovery lifted the dollar be-tween summer 1975 and summer 1976, propelling the currency by 28 per-cent against the British pound, 10 percent against the deutsche mark, and 6 percent against the yen. The notable rise versus the pound was especially driven by soaring inflation in the United Kingdom, lifting the retail price index by as high as 27.0 percent in August 1975.

THE FIRST DOLLAR CRISIS (1977–1979)

The U.S. dollar rebound of the mid-1970s came to a halt in summer 1976. What followed in the second half of the decade would be a five-year de-cline in the currency, unprecedented in the new post–gold standard era. Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign against Gerald Ford sought to lift the U.S. economy from its slowdown in the second half of 1976. Carter’s currency policy was famously based on the talking down of the U.S. dollar, especially through his outspoken Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal, who pressured the Fed into monetary policy easing. The slide was accel-erated in June 1977 when Blumenthal talked down the dollar after a meet-ing with his German and Japanese counterparts. The new policy sent the dollar tumbling more than 20 percent between January 1977 and October 1978, a dramatic plunge by postwar standards. Figure 2.3 shows how the

FIGURE 2.3 U.S. dollar drops nearly 40 percent against the Japanese yen as U.S.

officials talk down the currency.

dollar tumbled 38 percent against the Japanese yen as Japan’s trade sur-plus soared on its burgeoning exports industry. Figure 2.4 illustrates the 22 percent decline in the U.S. dollar index from its 1976 peak.

The dollar crisis was a vociferous manifestation of eroding market confidence in Carter’s economic policies despite the fact that U.S. inter-est rates were yielding substantially more than those overseas. While the United States had embarked on a gradual tightening policy starting in early 1977, Germany and Japan were in the midst of an easing campaign that lasted well into 1978. From summer 1977 to autumn 1978, U.S. interest rates nearly doubled from 5.9 percent to 9.5 percent. In contrast, German and Japanese rates fell from 4.5 to 3.5 percent and from 5 to 3.5 percent, respectively, tripling the yield advantage in favor of the U.S. dollar.

officials talk down the currency.

dollar tumbled 38 percent against the Japanese yen as Japan’s trade sur-plus soared on its burgeoning exports industry. Figure 2.4 illustrates the 22 percent decline in the U.S. dollar index from its 1976 peak.

The dollar crisis was a vociferous manifestation of eroding market confidence in Carter’s economic policies despite the fact that U.S. inter-est rates were yielding substantially more than those overseas. While the United States had embarked on a gradual tightening policy starting in early 1977, Germany and Japan were in the midst of an easing campaign that lasted well into 1978. From summer 1977 to autumn 1978, U.S. interest rates nearly doubled from 5.9 percent to 9.5 percent. In contrast, German and Japanese rates fell from 4.5 to 3.5 percent and from 5 to 3.5 percent, respectively, tripling the yield advantage in favor of the U.S. dollar.

PLEASE READ ALSO : OIL GLUT AND PRICE COLLAPSE (1981–1986) AND THE SUPER DOLLAR OF 1980–1984 THE WORLD’S THIRD OIL SHOCK

So why did the dollar damage occur when the U.S. currency had yielded substantially higher rates than its German and Japanese counter-parts? The answer lies in Carter’s policy of targeting a 4.9 percent unem-ployment rate, following the stagflation days of the Ford administration where unemployment breached 9 percent and inflation crossed over 11 per-cent. As Carter pursued his unemployment target via major fiscal stimuli, inflation headed back up and so did the budget deficit—the two bogey-men of financial markets. Inevitably, confidence in the dollar continued to erode.

So why did the dollar damage occur when the U.S. currency had yielded substantially higher rates than its German and Japanese counter-parts? The answer lies in Carter’s policy of targeting a 4.9 percent unem-ployment rate, following the stagflation days of the Ford administration where unemployment breached 9 percent and inflation crossed over 11 per-cent. As Carter pursued his unemployment target via major fiscal stimuli, inflation headed back up and so did the budget deficit—the two bogey-men of financial markets. Inevitably, confidence in the dollar continued to erode.

FIGURE 2.4 The 22 percent decline in the U.S. dollar index was less pronounced than the dollar’s damage against the yen, as Japan’s expanding trade surplus was a boon for the currency.

In November 1978, the United States mounted a massive joint interven-tion with Germany and Japan to buy dollars against foreign currencies. The move was supplemented with a 100-basis-point increase in the discount rate, the biggest in 45 years. The coordinated intervention proved limited in stabilizing the U.S. dollar. It wasn’t until the Fed rewrote the rules of monetary policy management to combat soaring inflation in late 1978 that the currency began to turn around.

SECOND OIL SHOCK (1978–1980)

An unusual period of stability in oil prices during the period 1976–1978 proved short-lived. Oil prices had averaged about $12 per barrel partly due to a firm dollar in 1976 and early 1977, while major industrialized economies averaged annual growth rates at a brisk 5 percent accompanied by lower levels of inflation from the 1974–1975 period. But the 1977–1979 dollar crisis prompted more price hikes from OPEC, which were further accelerated by an increasingly unstable political environment in Iran. Surg-ing social unrest in the second half of 1978 led to heated protests against the U.S.-backed Shah regime, culminating in the hostage crisis of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the Iranian Revolution of February 1979.

The combination of plummeting oil production in Iran and OPEC’s price hikes resulting from a falling U.S. dollar pushed up oil prices by more than 200 percent between 1979 and 1980, giving rise to the second oil shock in less than 10 years. Just as in 1973–1974, the oil shock of 1979–1980 would trigger soaring inflation rates, which eventually eroded GDP growth, send-ing the world into recession. The relationship is cogently illustrated in Fig-ure 2.5, where the three major oil shocks (1973–1974, 1978–1980, and the first Gulf War of 1989–1990) prompted the recurring pattern of mounting inflation followed by a contraction in economic growth.

In November 1978, the United States mounted a massive joint interven-tion with Germany and Japan to buy dollars against foreign currencies. The move was supplemented with a 100-basis-point increase in the discount rate, the biggest in 45 years. The coordinated intervention proved limited in stabilizing the U.S. dollar. It wasn’t until the Fed rewrote the rules of monetary policy management to combat soaring inflation in late 1978 that the currency began to turn around.

SECOND OIL SHOCK (1978–1980)

An unusual period of stability in oil prices during the period 1976–1978 proved short-lived. Oil prices had averaged about $12 per barrel partly due to a firm dollar in 1976 and early 1977, while major industrialized economies averaged annual growth rates at a brisk 5 percent accompanied by lower levels of inflation from the 1974–1975 period. But the 1977–1979 dollar crisis prompted more price hikes from OPEC, which were further accelerated by an increasingly unstable political environment in Iran. Surg-ing social unrest in the second half of 1978 led to heated protests against the U.S.-backed Shah regime, culminating in the hostage crisis of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the Iranian Revolution of February 1979.

The combination of plummeting oil production in Iran and OPEC’s price hikes resulting from a falling U.S. dollar pushed up oil prices by more than 200 percent between 1979 and 1980, giving rise to the second oil shock in less than 10 years. Just as in 1973–1974, the oil shock of 1979–1980 would trigger soaring inflation rates, which eventually eroded GDP growth, send-ing the world into recession. The relationship is cogently illustrated in Fig-ure 2.5, where the three major oil shocks (1973–1974, 1978–1980, and the first Gulf War of 1989–1990) prompted the recurring pattern of mounting inflation followed by a contraction in economic growth.

0 Response to "FIRST OIL SHOCK (1973–1974), THE FIRST DOLLAR CRISIS (1977–1979) AND SECOND OIL SHOCK (1978–1980)"

Post a Comment