2000 TIGHT FED, SOARING FOREIGN FLOWS BOOST THE GREENBACK TO 2001: RECESSION FAVORS DOLLAR DUE TO AGGRESSIVE FED CUTS

2000: TIGHT FED, SOARING FOREIGN FLOWS BOOST THE GREENBACK

As the world economy gathered further strength in the aftermath of the 1997–1999 market crises, investors grew bolder in their appetite for stocks, bolstering their already solid interest in U.S. assets and the U.S. cur-rency. (See Figure 3.5.) But despite strengthening global growth, metals failed to sustain the solid performance of 1999 as paper currencies proved

As the world economy gathered further strength in the aftermath of the 1997–1999 market crises, investors grew bolder in their appetite for stocks, bolstering their already solid interest in U.S. assets and the U.S. cur-rency. (See Figure 3.5.) But despite strengthening global growth, metals failed to sustain the solid performance of 1999 as paper currencies proved

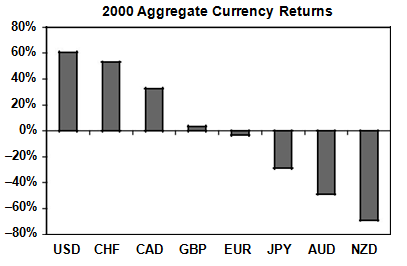

FIGURE 3.5 Massive foreign purchases of U.S. stocks in 2000 powered the dollar to the top-ranking position of aggregate currency returns.

triumphant due to interest rate hikes throughout the industrialized world. Oil prices, meanwhile, were up as much as 48 percent on the year in the third quarter before cancelling nearly all of the gains in the fourth quarter.

To tackle rising inflation, the Federal Reserve raised rates by 100 bps to a nine-year high of 6.5 percent, while the Bank of England and European Central Bank raised rates by 50 bps and 175 bps to 6 percent and 4.75 percent respectively. There were also rate hikes from Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and Switzerland.

The technology stocks bubble combined with accelerating growth gave the USD its strongest showing among the eight currencies, while exacerbating the lackluster performance in metals. Consequently, the oil-dependent Canadian dollar showed the third-best performance, tracking oil’s rise. The New Zealand dollar remained the worst performer for the second consecutive year due to the nation’s high trade deficit, while the aussie was dragged down by a 3 percent decline in copper prices. The yen made a sharp U-turn, losing 29 percent as global investors mostly sold off the stocks they had purchased the prior year. (See Figure 3.6.)

U.S. Dollar: +61 percent Interest rate hikes, surging capital flows, strong growth, and rising inflation were all reasons for the dollar’s stellar performance in 2000. After rising 59 percent to a record $107.9 billion in 1999, net foreign purchases of U.S. stocks rose 39 percent to a new record of $174.9 billion in 2000, chasing the bull market in technology stocks.

But U.S. stocks weren’t the only destination of record foreign flows. Figure 3.7 shows the breakdown of foreign flows into U.S. assets between

triumphant due to interest rate hikes throughout the industrialized world. Oil prices, meanwhile, were up as much as 48 percent on the year in the third quarter before cancelling nearly all of the gains in the fourth quarter.

To tackle rising inflation, the Federal Reserve raised rates by 100 bps to a nine-year high of 6.5 percent, while the Bank of England and European Central Bank raised rates by 50 bps and 175 bps to 6 percent and 4.75 percent respectively. There were also rate hikes from Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and Switzerland.

The technology stocks bubble combined with accelerating growth gave the USD its strongest showing among the eight currencies, while exacerbating the lackluster performance in metals. Consequently, the oil-dependent Canadian dollar showed the third-best performance, tracking oil’s rise. The New Zealand dollar remained the worst performer for the second consecutive year due to the nation’s high trade deficit, while the aussie was dragged down by a 3 percent decline in copper prices. The yen made a sharp U-turn, losing 29 percent as global investors mostly sold off the stocks they had purchased the prior year. (See Figure 3.6.)

U.S. Dollar: +61 percent Interest rate hikes, surging capital flows, strong growth, and rising inflation were all reasons for the dollar’s stellar performance in 2000. After rising 59 percent to a record $107.9 billion in 1999, net foreign purchases of U.S. stocks rose 39 percent to a new record of $174.9 billion in 2000, chasing the bull market in technology stocks.

But U.S. stocks weren’t the only destination of record foreign flows. Figure 3.7 shows the breakdown of foreign flows into U.S. assets between

FIGURE 3.6 U.S. dollar pairs dominated the best-performing foreign exchange rates of 2000.

FIGURE 3.7 The year 2000 was the only year when foreign purchases of U.S. assets rose in each asset class (stocks, Treasuries, corporate bonds, and Agency bonds over the prior year).

1989 and 2007, illustrating that 2000 was the only year with an increase in net purchases of U.S. stocks, corporate bonds, Treasury securities (bills and bonds), and agency bonds (bonds of local agencies and municipali-ties). Every other year in the chart shows a decrease in at least one of these U.S. asset classes. Such a remarkable trend in 2000 proved to be the backbone of the dollar’s resulting 61 percent increase against AUD, CAD, CHF, EUR, GBP, JPY, and NZD.

The U.S. presidential elections of November 2000 also had consid-erable impact on currency markets, as the victory of Republican candi-date George W. Bush over Democrat candidate Al Gore was cheered by U.S. markets due to market-friendly economic policies of the Republi-can Party. The positive impact on the dollar was especially highlighted during the several reports that erroneously announced victory for Gore, whose planned tax hikes were seen as negative for stocks and the cur-rency. The dollar then rallied strongly during the recount period in mid-November with each subsequent news story rectifying the claim of a Gore victory.

Swiss Franc: +53 percent The Swiss franc proved an unlikely second-highest performer in 2000, despite low interest rates and relatively small capital markets. But the highest GDP growth rate in over a decade and a doubling of interest rates to 3.5 percent stood in the way of carry trades betting on a weakening and low-yielding franc. Swiss GDP growth nearly tripled to 3.6 percent, enabling the Swiss National Bank to raise rates without worrying about restraining growth. The growth story was also bolstered by robust neighboring economies, such as the Eurozone and the United Kingdom both growing by 3.8 percent, rates not seen in over a decade.

But the franc’s gains were also related to risk appetite. Once global equities peaked in the second quarter of 2000 and the tech rally began to falter, stocks grew more volatile. What followed was a decline of 42 percent and 18 percent in the NASDAQ and S&P 500, respectively, from September to December 2000, which prompted currency traders to seek the safety of the franc, as the Swiss economy remained sheltered from the slowing U.S. economy and bolstered by a growing European recovery. The franc par-ticularly rose across the board in November and December when market volatility was heightened by the uncertainty surrounding the U.S. presiden-tial election and the intensifying sell-off in Wall Street amid the slowing U.S. economy.

Canadian Dollar: +33 percent The Canadian dollar ranked third-highest returning currency for the second straight year, benefiting from a combination of accelerating growth, rising interest rates, and a temporary

jump in oil prices. The 45 percent summer price increase to a 10-year high of $37 per barrel sufficed in spurring the CAD higher for the rest of the year despite a retreat in oil later in December. The oil pullback in late fourth quarter gave oil a modest 4 percent increase for the year, but the $20 price spike between May and September 2000 was a boon for the oil-dependent loonie.

On the growth side, Canada’s GDP maintained a growth rate of 5.2 percent, following 5.5 percent in 1999, well above the 2.1 percent average of 1989–1998. In addition to the oil and growth windfall, the loonie was boosted by a 100 bps increase in overnight interest rates to 6 percent, the highest in five years.

British Pound: +3.5 percent Sterling’s lackluster 3.5 percent cumu-lative return against the other seven major currencies shows that despite the United Kingdom’s stellar GDP growth of 3.8 percent and the Bank of England’s (BoE) rate hikes to 6 percent, it was not enough to prevent the currency from losing 7 percent against the USD, 4 percent against CAD and CHF, and 0.8 percent against EUR. Speculators also began exiting long GBP positions after midyear when the BoE’s first-quarter tightening was perceived to have begun threatening a protracted slowdown. Indeed, the Bank of England joined the Fed in January 2001 to begin an extended eas-ing campaign.

Euro: -3.2 percent The 175-point rate hikes from the ECB proved too little too late in stemming the euro’s losing tide, whose intensification be-gan amid eroding credibility with ECB policy. Recall that a large reason for the euro’s aggregate 74 percent tumble against the major seven curren-cies in 1999 was the excessively hawkish ECB policy. While the ECB was mandated to keep inflation below the 2 percent ceiling, inflation remained below that ceiling throughout the year—despite rising from under 1.0 per-cent to 1.8 percent.

Foreign exchange markets suspected that the ECB was behind the curve in shoring up growth, especially when it raised rates by 225 bps from fall 1999 to fall 2000. Rather than boosting the currency, the rate hikes were punishing the already struggling German and Italian economies. In 2000, inflation exceeded the 2.0 percent ceiling while money supply growth re-mained well above the ECB’s policy pillar of maintaining monetary growth at an annual three-month average of 4.5 percent.

The bulk of the euro’s losses stemmed from an excessively restrictive monetary policy and a central bank largely deemed to be inexperienced, especially as differing points of view and statements from within the pol-icy makers started to be more prominent. That contrasted with the cen-tral banks of the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom, whose

1989 and 2007, illustrating that 2000 was the only year with an increase in net purchases of U.S. stocks, corporate bonds, Treasury securities (bills and bonds), and agency bonds (bonds of local agencies and municipali-ties). Every other year in the chart shows a decrease in at least one of these U.S. asset classes. Such a remarkable trend in 2000 proved to be the backbone of the dollar’s resulting 61 percent increase against AUD, CAD, CHF, EUR, GBP, JPY, and NZD.

The U.S. presidential elections of November 2000 also had consid-erable impact on currency markets, as the victory of Republican candi-date George W. Bush over Democrat candidate Al Gore was cheered by U.S. markets due to market-friendly economic policies of the Republi-can Party. The positive impact on the dollar was especially highlighted during the several reports that erroneously announced victory for Gore, whose planned tax hikes were seen as negative for stocks and the cur-rency. The dollar then rallied strongly during the recount period in mid-November with each subsequent news story rectifying the claim of a Gore victory.

Swiss Franc: +53 percent The Swiss franc proved an unlikely second-highest performer in 2000, despite low interest rates and relatively small capital markets. But the highest GDP growth rate in over a decade and a doubling of interest rates to 3.5 percent stood in the way of carry trades betting on a weakening and low-yielding franc. Swiss GDP growth nearly tripled to 3.6 percent, enabling the Swiss National Bank to raise rates without worrying about restraining growth. The growth story was also bolstered by robust neighboring economies, such as the Eurozone and the United Kingdom both growing by 3.8 percent, rates not seen in over a decade.

But the franc’s gains were also related to risk appetite. Once global equities peaked in the second quarter of 2000 and the tech rally began to falter, stocks grew more volatile. What followed was a decline of 42 percent and 18 percent in the NASDAQ and S&P 500, respectively, from September to December 2000, which prompted currency traders to seek the safety of the franc, as the Swiss economy remained sheltered from the slowing U.S. economy and bolstered by a growing European recovery. The franc par-ticularly rose across the board in November and December when market volatility was heightened by the uncertainty surrounding the U.S. presiden-tial election and the intensifying sell-off in Wall Street amid the slowing U.S. economy.

Canadian Dollar: +33 percent The Canadian dollar ranked third-highest returning currency for the second straight year, benefiting from a combination of accelerating growth, rising interest rates, and a temporary

jump in oil prices. The 45 percent summer price increase to a 10-year high of $37 per barrel sufficed in spurring the CAD higher for the rest of the year despite a retreat in oil later in December. The oil pullback in late fourth quarter gave oil a modest 4 percent increase for the year, but the $20 price spike between May and September 2000 was a boon for the oil-dependent loonie.

On the growth side, Canada’s GDP maintained a growth rate of 5.2 percent, following 5.5 percent in 1999, well above the 2.1 percent average of 1989–1998. In addition to the oil and growth windfall, the loonie was boosted by a 100 bps increase in overnight interest rates to 6 percent, the highest in five years.

British Pound: +3.5 percent Sterling’s lackluster 3.5 percent cumu-lative return against the other seven major currencies shows that despite the United Kingdom’s stellar GDP growth of 3.8 percent and the Bank of England’s (BoE) rate hikes to 6 percent, it was not enough to prevent the currency from losing 7 percent against the USD, 4 percent against CAD and CHF, and 0.8 percent against EUR. Speculators also began exiting long GBP positions after midyear when the BoE’s first-quarter tightening was perceived to have begun threatening a protracted slowdown. Indeed, the Bank of England joined the Fed in January 2001 to begin an extended eas-ing campaign.

Euro: -3.2 percent The 175-point rate hikes from the ECB proved too little too late in stemming the euro’s losing tide, whose intensification be-gan amid eroding credibility with ECB policy. Recall that a large reason for the euro’s aggregate 74 percent tumble against the major seven curren-cies in 1999 was the excessively hawkish ECB policy. While the ECB was mandated to keep inflation below the 2 percent ceiling, inflation remained below that ceiling throughout the year—despite rising from under 1.0 per-cent to 1.8 percent.

Foreign exchange markets suspected that the ECB was behind the curve in shoring up growth, especially when it raised rates by 225 bps from fall 1999 to fall 2000. Rather than boosting the currency, the rate hikes were punishing the already struggling German and Italian economies. In 2000, inflation exceeded the 2.0 percent ceiling while money supply growth re-mained well above the ECB’s policy pillar of maintaining monetary growth at an annual three-month average of 4.5 percent.

The bulk of the euro’s losses stemmed from an excessively restrictive monetary policy and a central bank largely deemed to be inexperienced, especially as differing points of view and statements from within the pol-icy makers started to be more prominent. That contrasted with the cen-tral banks of the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom, whose

FIGURE 3.8 The euro’s intensifying sell-o? of 2000 prompted the ECB to inter-vene with other major central banks on at least four occasions.

governors at the time (Greenspan, Hayami, and George) were associated with respect and proven experience.

In the last week of January 2000, the euro broke below parity with the U.S. dollar, culminating a decline from its $1.1740 opening level a year ear-lier. EUR went on to lose 6 percent versus USD to reach an all-time low of 82.25 U.S. cents, prompting a series of concerted interventions by the European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada. There were four officially reported interventions be-tween September and November 2000, the last two of which took place one day before and after the closely contested U.S. presidential election so as to contain excessive dollar rally versus the euro. (See Figure 3.8.)

governors at the time (Greenspan, Hayami, and George) were associated with respect and proven experience.

In the last week of January 2000, the euro broke below parity with the U.S. dollar, culminating a decline from its $1.1740 opening level a year ear-lier. EUR went on to lose 6 percent versus USD to reach an all-time low of 82.25 U.S. cents, prompting a series of concerted interventions by the European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada. There were four officially reported interventions be-tween September and November 2000, the last two of which took place one day before and after the closely contested U.S. presidential election so as to contain excessive dollar rally versus the euro. (See Figure 3.8.)

PLEASE READ ALSO : 2001 RECESSION FAVORS DOLLAR DUE TO AGGRESSIVE FED CUTS

Japanese Yen: -29 percent The same factors prompting the yen’s outperformance of 1999 were also behind the currency’s 29 percent sell-off of 2000. Just as Japanese stocks were among the first to be snapped up by global fund managers during the global economic recovery of 1999, these were unloaded aggressively throughout 2000 as the global tech wreck turned into an all-around global market corrosion. Foreign investors sold a net 234.0 billion yen of Japanese stocks in 2000, following the record total net purchases of 11.9 trillion yen in 1999.

Australian Dollar: -49 percent The aussie’s underperformance of 2000 underlines the currency’s high correlation with copper prices, which

overrides the impact of growth and interest rates. Although GDP growth slowed from 4.4 percent in 1999 to 3.4 percent in 2000, it remained well above the 1989–1998 average of 3.3 percent. Yet it was the 3 percent de-cline in copper prices that weighed on the currency, following a 31 percent increase in 1999. The aussie’s losses especially intensified when a robust rally in the second quarter peaked in September at 16-year highs, before starting a 12 percent decline into the rest of the year. Consequently, the aussie tumbled to an all-time low against the USD, reaching the 50-cent fig-ure in November 2000, down from the February high of 67 cents. Copper’s decline in the fourth quarter emerged as slowing world growth was on the cusp of recession.

New Zealand Dollar: -69 percent The kiwi finished at the bottom of the return ranking for the second consecutive year as it remained hit by a mediocre environment for dairy prices and investors clustered the aussie and peripheral currencies across the board. Although New Zealand’s cur-rent account deficit stabilized from 6.2 percent of GDP in 1999 to 5.1 per-cent in 2000, it remained the highest among developed nations, especially as the global price environment for agriculture and dairy products turned lackluster in the second half of the year. GDP growth slowed to 3.9 percent from 4.3 percent.

0 Response to "2000 TIGHT FED, SOARING FOREIGN FLOWS BOOST THE GREENBACK TO 2001: RECESSION FAVORS DOLLAR DUE TO AGGRESSIVE FED CUTS"

Post a Comment