OIL FUNDAMENTALS IN THE CURRENCY MARKET FROM A GOLD STANDARD TO AN OIL STANDARD (1970S–1980S) AND OIL PRICE SHOCKS FUELED BY MOUNTING INFLATION, FALLING DOLLAR

The relationship between the most sought-after energy form and the Tworld’s reserve currency has invariably evolved via the intermedia-tion of world economic growth and its response to energy prices. Each of the global recessions of the mid-1970s, early 1980s, and early 1990s was triggered by an oil shock stemming from soaring petroleum prices. As those recessions impacted the U.S. economy, the dollar came under pressure.

But oil prices did not always play the lead role in the dollar-oil causal-ity. As this chapter will demonstrate, the tumbling dollar was a key factor in oil producers’ decision to raise oil prices during the early 1970s in order to cushion the impact of a falling purchasing power as the weak currency eroded the value of their dollar-denominated oil receipts. In those cases, a falling dollar triggered rising oil prices, which in turn resulted in a global in-flationary spiral and later a recession. As the Federal Reserve rushed to in-crease interest rates to counter the inflationary costs of high energy prices, U.S. yields gained in attractiveness, prompting the sharpest U.S. dollar rally in history.

But rising oil prices did not always boost the dollar. The arrival of al-ternative sources of energy, the rise of economic powers in the develop-ing world, and the convergence of global economies via capital flows con-tributed to changes in the demand/supply equation for oil as well as its in-fluence on different economies, whose currencies fluctuated significantly against the greenback. And no analysis of oil prices and the U.S. dollar can be undertaken without addressing the geopolitical events shaping the price of oil over the past half century, as well as the shifting dynamics in global

But oil prices did not always play the lead role in the dollar-oil causal-ity. As this chapter will demonstrate, the tumbling dollar was a key factor in oil producers’ decision to raise oil prices during the early 1970s in order to cushion the impact of a falling purchasing power as the weak currency eroded the value of their dollar-denominated oil receipts. In those cases, a falling dollar triggered rising oil prices, which in turn resulted in a global in-flationary spiral and later a recession. As the Federal Reserve rushed to in-crease interest rates to counter the inflationary costs of high energy prices, U.S. yields gained in attractiveness, prompting the sharpest U.S. dollar rally in history.

But rising oil prices did not always boost the dollar. The arrival of al-ternative sources of energy, the rise of economic powers in the develop-ing world, and the convergence of global economies via capital flows con-tributed to changes in the demand/supply equation for oil as well as its in-fluence on different economies, whose currencies fluctuated significantly against the greenback. And no analysis of oil prices and the U.S. dollar can be undertaken without addressing the geopolitical events shaping the price of oil over the past half century, as well as the shifting dynamics in global

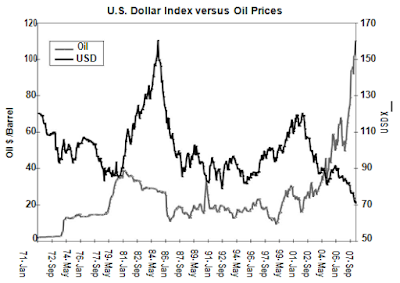

FIGURE 2.1 The inverse relationship between the U.S. dollar and oil was most striking during periods of protracted uptrends or downtrends in oil.

oil consumption and production. Finally, we will look at the relationship between the price of gold and oil over the past 30 years and how it helps investors assess the implications for the U.S. economy, interest rates, and the dollar (see Figure 2.1).

FROM A GOLD STANDARD TO AN OIL STANDARD (1970s–1980s)

The decline in the value of the dollar following the 1971 collapse of the gold-dollar exchange standard set up in Bretton Woods in 1944 played a vital role in fueling the upward spiral in oil prices of the first half of the 1970s.

Recall that during the Bretton Woods period, from 1944 until 1971, cen-tral banks converted their surplus dollars into gold in order to adjust for trade imbalances with their trade partners. The conversions were done at the fixed price of gold of US$35 per ounce. Oil prices, meanwhile, were mostly stable at about US$3.00 per barrel. But when Richard Nixon shut down the gold window, refusing to pay out nearly $300 million in ounces of

gold to countries holding U.S. dollars, U.S. trading partners were left with mountains of surplus dollars that were no longer exchangeable into gold at $35 per ounce. Oil producers were forced to convert their excess U.S. dol-lars by purchasing gold in the marketplace, driving both the fuel and the metal higher and sending the value of the dollar lower.

The resulting devaluation of the surplus dollars around the world was a rude awakening to oil producers who had been receiving gold for their oil since 1933. From January 1971 to July 1973, the dollar index (measured against a basket of six currencies) lost 25 percent of its value, prompting the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to initiate its first price-boosting campaign. In October 1973, oil became a weapon when Arab oil producers set up an oil embargo against supporters of Israel in the Arab-Israeli war, cutting exports and reducing output by over 25 per-cent, thus producing the first oil shock in history. By the time the embargo was lifted against the United States in March 1974, oil prices had quadru-pled to nearly $12 per barrel, triggering a global economic slowdown and inflation over the next three years.

PLEASE READ ALSO : FIRST OIL SHOCK (1973–1974), THE FIRST DOLLAR CRISIS (1977–1979) AND SECOND OIL SHOCK (1978–1980)

In 1975, OPEC agreed to sell its oil exclusively for U.S. dollars, giving the depreciating U.S. currency the new role of world reserve currency and establishing oil as the preeminent energy resource of the world. While the Bretton Woods era of the 1950s to 1960s was known as the gold-backed standard, the 1970s and 1980s ushered in a de facto oil-dollar standard. It is no coincidence that the dollar value of the world’s petroleum imports as a percentage of total fossil fuel imports fell from an average of 61 percent in the 1950s to 52 percent during the 1960s, before soaring to 70 percent in the 1970s. Unlike in the 1950s to 1960s when oil prices remained steady below $2.00 per barrel, partly due to the stable dollar/gold relationship of $35 per ounce, oil prices shot up in the 1970s as a result of the dollar’s break from its fixed price against gold.

oil consumption and production. Finally, we will look at the relationship between the price of gold and oil over the past 30 years and how it helps investors assess the implications for the U.S. economy, interest rates, and the dollar (see Figure 2.1).

FROM A GOLD STANDARD TO AN OIL STANDARD (1970s–1980s)

The decline in the value of the dollar following the 1971 collapse of the gold-dollar exchange standard set up in Bretton Woods in 1944 played a vital role in fueling the upward spiral in oil prices of the first half of the 1970s.

Recall that during the Bretton Woods period, from 1944 until 1971, cen-tral banks converted their surplus dollars into gold in order to adjust for trade imbalances with their trade partners. The conversions were done at the fixed price of gold of US$35 per ounce. Oil prices, meanwhile, were mostly stable at about US$3.00 per barrel. But when Richard Nixon shut down the gold window, refusing to pay out nearly $300 million in ounces of

gold to countries holding U.S. dollars, U.S. trading partners were left with mountains of surplus dollars that were no longer exchangeable into gold at $35 per ounce. Oil producers were forced to convert their excess U.S. dol-lars by purchasing gold in the marketplace, driving both the fuel and the metal higher and sending the value of the dollar lower.

The resulting devaluation of the surplus dollars around the world was a rude awakening to oil producers who had been receiving gold for their oil since 1933. From January 1971 to July 1973, the dollar index (measured against a basket of six currencies) lost 25 percent of its value, prompting the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to initiate its first price-boosting campaign. In October 1973, oil became a weapon when Arab oil producers set up an oil embargo against supporters of Israel in the Arab-Israeli war, cutting exports and reducing output by over 25 per-cent, thus producing the first oil shock in history. By the time the embargo was lifted against the United States in March 1974, oil prices had quadru-pled to nearly $12 per barrel, triggering a global economic slowdown and inflation over the next three years.

In 1975, OPEC agreed to sell its oil exclusively for U.S. dollars, giving the depreciating U.S. currency the new role of world reserve currency and establishing oil as the preeminent energy resource of the world. While the Bretton Woods era of the 1950s to 1960s was known as the gold-backed standard, the 1970s and 1980s ushered in a de facto oil-dollar standard. It is no coincidence that the dollar value of the world’s petroleum imports as a percentage of total fossil fuel imports fell from an average of 61 percent in the 1950s to 52 percent during the 1960s, before soaring to 70 percent in the 1970s. Unlike in the 1950s to 1960s when oil prices remained steady below $2.00 per barrel, partly due to the stable dollar/gold relationship of $35 per ounce, oil prices shot up in the 1970s as a result of the dollar’s break from its fixed price against gold.

OIL PRICE SHOCKS FUELED BY MOUNTING INFLATION, FALLING DOLLAR

Up to this day, many still attribute the quadrupling of oil prices in 1974 to OPEC’s oil embargo and its increased political dominance. But in fact, it was the surging inflation of the late 1960s into the early 1970s and the falling value of the U.S. dollar that drove OPEC’s decision to raise prices so as to make up for changes in real purchasing power. Recall that the pressure on the dollar escalated as early as the late 1960s when the cost of financing the Vietnam War and the Cold War drove up the balance of payments deficit. As dollars poured out of the United States and liabilities to foreign central banks soared, the world was flush with dollars while the U.S. gold stock was being depleted. Nixon’s decision to shut the gold window in August 1971 ended the dollar’s convertibility onto gold, prompting a collapse in the international financial system that was based on confidence in the U.S. dollar.

In December 1971, the dollar was devalued from the agreed-upon price of $35 per ounce of gold to $44.2 per ounce. A series of devaluations in 1972 culminated in the end of the Bretton Woods System in February 1973. The dollar became freely traded and freely sold. From January 1971 to February 1973, the dollar dropped 26.0 percent against the yen, 4.0 percent against the British pound, and 17 percent against the Deutsche mark.

0 Response to "OIL FUNDAMENTALS IN THE CURRENCY MARKET FROM A GOLD STANDARD TO AN OIL STANDARD (1970S–1980S) AND OIL PRICE SHOCKS FUELED BY MOUNTING INFLATION, FALLING DOLLAR"

Post a Comment